La Union Surfers is a series that RJ Fernandez produced over a decade ago, on weekend commutes to Ilocos from Manila, where she was working as a commercial photographer's assistant.

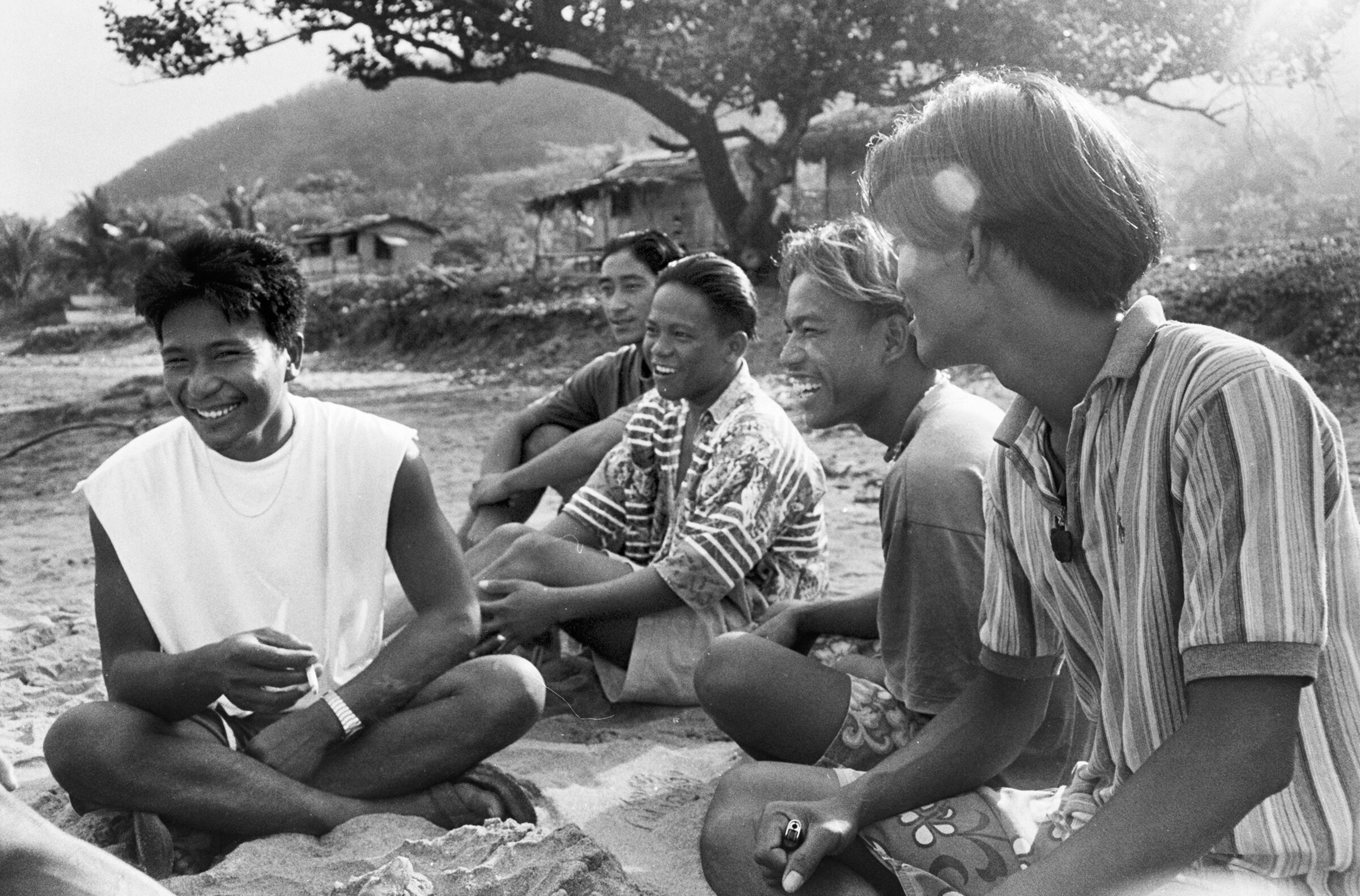

The collaboration with the Ilocano boys happened spontaneously, as the photographer would join the lineup in the water, astride her board early on Saturday mornings. The scene was pretty compact at this time – on a good day, you would have about seven locals from the neighbouring villages. In the daytime, some would work as fishermen.

This was at the real beginnings of the Filipino surfing scene, now clustered with surf clubs and brand flags. Apparently, this is how it happened: a few Australians and Americans travelled over on holiday, and left their boards behind once they left.

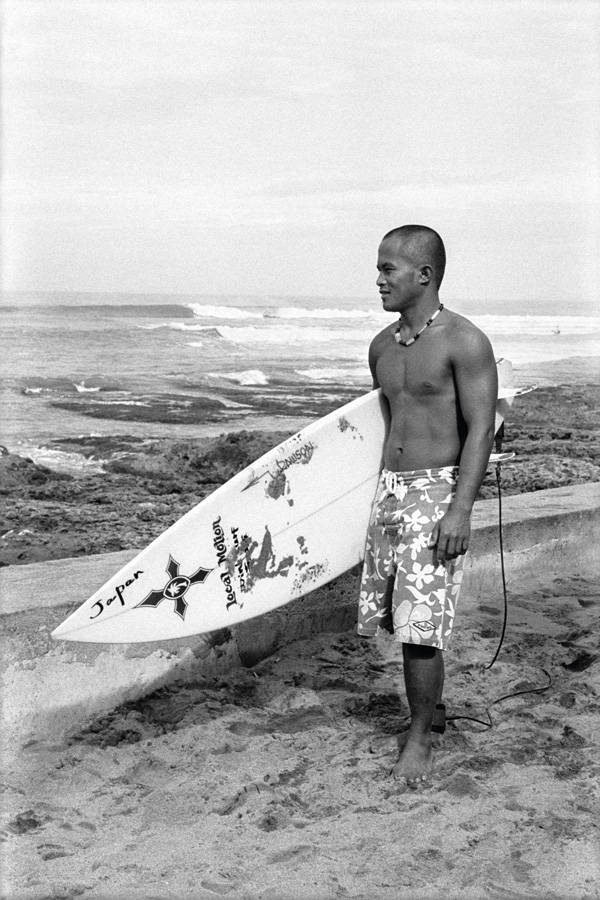

The first element to consider is the familiarity of the images – in effect, a false familiarity. The photographs allude to an imagined history of surf, while at the same time they remind of traditional black and white documentary photography. The former is a comparison that occurs via the “so-they-say” mechanism: surfing, that originated probably one thousand years ago in Hawaii has been recorded for centuries, starting with Captain James Cook's written accounts or the early engravings, leading up to the idyllic images of the first Californians to reintroduce the sport to its birthplace – literally a handful of haoles trying to escape the rigid life-schedule of commitments that awaitedthem at home in post-war America (thus the intrinsic “rebelliousness” of surfers from this time: they didn't “care” for the alternative). This was followed by more recent footage of wet-suited silhouettes skidding up and down massive rocks of water in Hawaii, America, Bali, at impossible speeds – the new generations of jet-ski-powered riders. To trace an effective image progression from the origins of this sport to today is difficult: frontal portraits of men and their boards in a traditional documentary format like the ones by Fernandez are supplanted by action shots and panoramic views. Indeed portraiture was not what surfing photography was about, at least at its most “natural” during the 40s and 50s.

Surfing is not a real sport: it doesn't have scores, game-times or winners – it's a practice or simply something you do – there is nothing to achieve from it in a quantitative way. It's a process, like a relationship, that inevitably swells and changes, progresses and regresses without any apparent aim. The learning involved is not cumulative - if you can ride this giant it doesn't mean you will not be wiped out by the next one. Everything is constantly changing, and the lure lies in the ability to “adapt” fast enough, smartly enough to master yet another wave, get to know it sufficiently and then see it break on the shore – volcanic rocks in this case.

Fernandez' photographs function as documents, if seen within the field of anthropological research. Emblematically, they provide information about the individual and the surfers as a group. They include aspects of the surrounding landscape and some insight about the societal conditions (two images from the series are taken with housing in the background, a hint to the domestic environment of their seaside community). The black and white film doesn't allow for distracting elements, such as the allure of seaside landscape's colours. The details are crisp and effective – they function as clues that direct away from the surfing topic. Surfing in fact functions as an expedient to approach more pressing issues regarding the migration of forms, integration of customs, perceptions of history that seem overlapping and paradoxical. This element of apparent paradox, that debunks all expectations of history as a linear, hierarchical, fact-and-hero dominated narrative, is essential to Fernandez' work, thatlargely reflects on issues of societal evolution and historical mismatch. The crux of this series is that the different elements are replicable in other narratives/histories/systems. As the surfers' presence necessarily recall the history of surf, so the presence of the settlements in the background can allude to anthropological research. The project taps into work belonging to so many disciplines, from anthropology, as mentioned (bearing in mind its origins as a western science aiming to analyse social structures and practices, to then reflect/deflect from one's own); archaeology, intended as that discipline of ruins that has covered so much ground as to dig into contemporary waste (there is indeed , an archaeology of the immediate past, speeding up the pace with which the past takes its terrain); “humanist” photography, following the pillars of 20thcentury photography classes, from Bresson's peasants to Arbus' freaks, depicted in a tender way, in-between familiarity and the responsibility of crystallizing a human scene that is necessarily temporary, like all things.

Comparison with contemporary footage found on the internet of La Union's surf spots, testifies that Fernandez' scenes inevitably belong to the past, as surfing schools and sponsors have modified the quasi-early-Hawaiian scene of the early days, introducing elements of competition and showmanship, an entirely different approach to an activity that per-se is atemporal, horizontal and intuitive.

Things can be said about the fragile time-ecology represented by both the surfing practice as a disinterested relationship with the sea, and the slow-paced, cyclical rhythm of self-sustainable seaside communities, that nevertheless were able to be integrated within a 20th century growing economy. The search for a language to articulate historical narratives that don't fit into a traditional, hierarchical, chronological interpretation of time is a pressing issue for many disciplines concerning the “past”, as much as it is at stake in Fernandez' work, that branches out to different strategies of documentary, and to topics that can provide alternative insights to cultural phenomena that are far more layered and complex, more horizontal.

This early project strategically opens up to a dynamic of interchangeable elements: objects, customs or activities as in this case, can move freely from subject to signifier, bringing allusions to the foreground, exchanging narratives between disciplines and counter-historical collective memories. The La Union Surfers is the first in a line of projects that unpick different elements pertinent to the case of the Philippines: free-standing projects spanning from portraiture in rural areas, documentation of artefacts and organic elements, to land surveys of mining districts in northern Luzon. Each of these is an examination of the arrangement of personal spaces within broader socio-political narratives, through which the intention to report on the making of culture in her home country solidifies.

Catherine Borra